Once the routine of solidly loud fingers with consistently quiet thumb is well established in the right hand, additional activities are helpful to further build on this technique (see first post on Tremolo).

As these activities are best practiced with the actual piece (rather than over a symmetrical, moveable chord), I'll take a moment to describe how I like my students to learn (the left-hand part of) tremolo pieces.

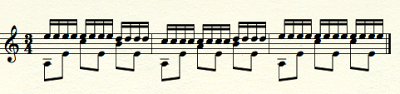

As the technique itself is problematic and therefore distracting, I ask them to "dumb it down" and play each unit of tremolo as two even 16th notes, m-i, instead of four, in the following pattern:

This way, they can concentrate on what the left hand actually has to do, facilitating a much quicker learning process.

This way, they can concentrate on what the left hand actually has to do, facilitating a much quicker learning process.

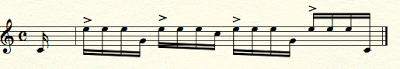

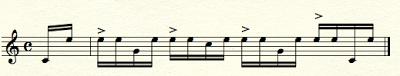

The next important skill is to learn to isolate (play loudly with) each finger in turn, while playing quietly with the remaining fingers. The easiest way to do it is to put the loud finger on the beat (play the following exercises with p-a-m-i pattern), first with a:

This exercise may seem counterintuitive, as in the end, we desire a uniform volume and tone from our fingers. But it is actually in the development of this odd internal accent series that we teach our hand the requisite control to keep the notes even. I'd recommend that this excercise be used while playing the piece, once through, in each form. Do so with a metronome going to guarantee clarity of pulse and emphasis.

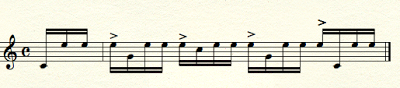

Next, it is important to develop the ability to smoothly speed up and slow down the tremolo, without sacrificing the distinct volume difference between fingers and thumb. Since this is a musical, interpretive device, it is most productively done in the piece also, over the course of a specific phrase.

Identify a phrase. Play only that phrase, starting very slowly, speeding up ever so gradually, until, at the top of the phrase, the tremolo is quite fast, then gradually slow it down again until, at the phrase's end, it is slowed to a halt, as in this excerpt from Barrios' Un Sueño en la Floresta:

In actual performance you might or might not play the phrase like that, or it might be hinted at, but with much more subtlety, but the skill to control a really big accel-decel is important to cultivate in either case. Further, you might discover some beautiful moments in the piece this way that are only revealed through such a vigorous rubato.

The effect of a long, truly gradual accel or decel always reminds me of the sound produced by a playing card clothespinned to the bicycle wheel frame so it sticks into the spokes. Slowing down creates a beautifully modulated ritard with every subdivision articulated equally. (That was me, age 9, high handlebars and banana seat...)

Getting your tremolo to speed up or slow down with equal precision and uniformity takes some rehearsal but is well worth it. After all, tremolo pieces tend to be in the romantic style. If you can't use rubato in this repertoire, where can you? Further, there is a direct correlation between tremolo and arpeggio, and by extension, all right hand technique. In other words, the benefits of these excercises are broad, not specific.

In any case, the critical element in the accel-decel activity is that the effect is perfectly gradual, or smooth. It needs to be equally finely calibrated speeding up and slowing down, all while maintaining a very clear difference in volume between the thumb and the tremolo notes. Repeat the gesture over the course of each phrase, individually. You'll be amazed at how beautiful it sounds once you develop your phrase-based tremolo rubato!

Tremolo III: tone, true legato and complex accompaniment.